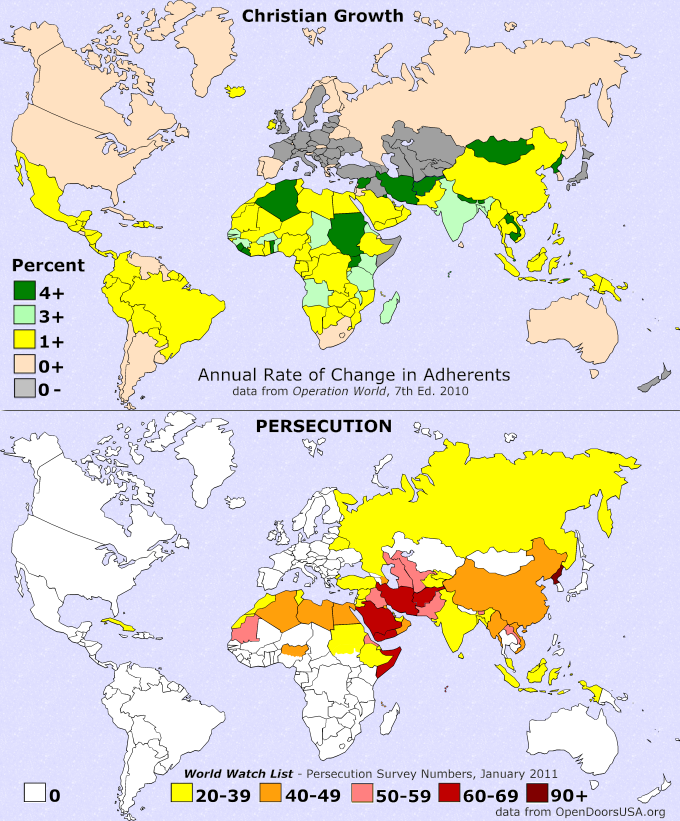

What do President Ahmadinijad in Iran and the Americans in Afghanistan have in common? Both are presiding over the world’s fastest growing Christian populations. In Iran, the Evangelical population is growing annually at 19.6 %. In Afghanistan, the rate is 16.7%.1

Some scholars theorize that persecution may have something to do with the growth.

Under Chairman Mao and Chinese Communism, professing Christians in China grew from 1.5 million in 1970 to 65 million in just twenty years.2 Fed to lions and hunted into the catacombs, Christianity gradually grew to dominate the Roman Empire.3

Persecution and exponential Christian growth often coincide. However, persecution often coincides with diminishing Christianity. For example, statistics on Christianity in Iraq are reversed from what they are in Iran and Afghanistan. Although Iraq is like Afghanistan in featuring both persecution and American presence, its Christian population is declining by 2.4% annually.4

Christianity was once the dominant religion across North Africa, through the Middle East, and up into Asia Minor (modern day Turkey). European Christians were once a small minority of all the Christians in the world. In 1050, Asia Minor, the land of the seven churches of the book of Revelation, boasted 373 ecclesiastical regions and was nearly 100 percent Christian. 400 years later, ecclesiastical regions in Asia Minor had dropped to three, and Christian population had dropped to less than 15 percent.5 Turkey today is nearly all Muslim and less than a quarter of a percent Christian.6

But it’s not only Islam that often displaces Christianity. During the time of nearly 300 years of persecution in Rome, Christians in Persia enjoyed relative freedom and were on their way to becoming the majority religion. Then after Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire more than 190,000 Christians were martyred in Persia over the next 40 years.7

Christianity was established in China and then eliminated at least twice. Relics and inscriptions show that Christians were present, free, and growing in China during the Tang Dynasty (618-907), but when that dynasty disappeared so did the Christians.8 Franciscan friars established a Christian presence in China during the years of Mongol rule (1271-1368), but they and their ministry results disappeared after the Ming Dynasty took over (1368).9

Christianity arrived in Japan with outside trade (Portuguese in 1542), and it grew to number around 300,000 within 50 years. But in 1587 Japan expelled all its foreigners, and, in 1614, Christians came under intense persecution.10 When Japan allowed missionaries back in 1858, what they found to have survived was some barely recognizable Christian traditions in a handful of remote fishing and island communities.11

I have a theory that explains why persecution sometimes coincides with Christian growth and sometimes coincides with Christian decline.

Martyrs who are in the socio-economic and ethno-linguistic group of their killers become a persuasive Christian testimony, but the testimony of martyrs who are in a different socio-economic and ethno-linguistic group has no significant impact on their killers.

This theory is a corollary to the “reached” and “unreached” people group categories championed by Ralph Winter and popularized at the 1974 International Congress on World Evangelization held in Lausanne, Switzerland.12

Winter and others like Donald McGavran and Cameron Townsend, the founder of Wycliffe, noticed that Christianity tends to spread within durable groups of people that have a natural affinity for one another until it reaches barriers of acceptance and understanding that exist between groups that have different identities and allegiances.

Thus a “reached people group” is one within which a sufficient number of indigenous Christians have the resources, vision, and ability to continue evangelizing their own people without meeting barriers of acceptance and understanding.

An “unreached people group” is a durable ethno-socio-linguistic unit featuring common identity and allegiance that lacks the people, resources, vision, and ability to self evangelize. Until someone from outside the group takes the gospel across the barriers of acceptance and understanding, that group will remain “unreached.”

Tertullian wrote on Roman persecution that the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church. He saw Christians killed for their faith, and he saw its effects on the society that was killing them.13 He was watching unbelievers within his people group killing believers who were among them – people with the same language, heritage, music, holidays, food, clothing, customs, courtesies, clothing, and living conditions.

The persecution that is happening today (in parts of China, Iran, and Afghanistan) where Christianity is growing occurs between people within the same ethno-socio-linguistic group.

However, the persecution that is happening today where Christianity is diminishing occurs between people groups. In Iraq, the unreached people group (Arab) is prevailing over the reached one (Assyrian).

Sometimes violence between reached and unreached people groups works in Christianity’s favor. Conquistadors established Christianity in Latin America,14 and Charlemagne conquered and then converted many pagan tribes of Western Europe.15 But in Egypt, Turkey, Persia, China, and Japan, power and history favored either the outside Arab and Turkic people groups invading or the inside people groups defending pagan culture.

When Christians become embedded in a people group like yeast in dough, then the heat of persecution helps them mature, propagate, and transform the loaf, but when Christians remain distinct from a people group like chocolate chips in a cookie, then the heat of persecution makes them melt away.

END NOTES:

1. Operation World 7th Edition by Jason Mandryk, Biblica Pub., 2010, p. 916.

2. World Christian Encyclopedia 2nd Edition, Oxford Univ. Press, 2001, vol. 1, p. 191.

3. The Church in History by B. K. Kuiper, Eerdmans Pub. Co., 1951, pp. 7-13.

5. The Lost History of Christianity by Philip Jenkins, HarperCollins Pub., 2008, p. 23.

7. Exploring Church History by Perry Thomas, World Pub., 2005, pp. 16-17.

8. The History of Christianity in Asia by Samuel Moffett, Orbis Books, 1998, vol. 1, pp. 288-314.

9. The History of Christianity in Asia, pp. 471-475.

10. A History of Christian Missions by Stephen Neill, Penguin Books Ltd., 1964, pp. 133-138.

11. The Lost History of Christianity, pp. 36-37.

12. “On the Cutting Edge of Mission Strategy” by C. Peter Wagner in Perspectives on the World Christian Movement: A Reader 4th Edition, William Carey Library, 2009, p. 578.

13. Exploring Church History, p. 13.

Act Beyond

Act Beyond http://www.faithandwar.org

http://www.faithandwar.org Mark Durie's Blog

Mark Durie's Blog Military Missions Network

Military Missions Network The Christian Fighter Pilot

The Christian Fighter Pilot The Navy Christian

The Navy Christian