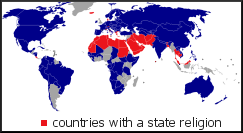

A Western culture that separates the relevance of spiritual and material realities as aggressively as it separates church and state handicaps itself at defining torture and interrogating terrorists. Here is how.

A Western culture that separates the relevance of spiritual and material realities as aggressively as it separates church and state handicaps itself at defining torture and interrogating terrorists. Here is how.

Our first of four sons was born in 1984, and in 1985 Dr. James Dobson wrote his classic book on raising “strong willed children.” His advice on “shaping the will without wounding the spirit” became a common sense guideline that my wife and I used for discipline. It fits with the way that God treats us. He often sends trials and tribulations to break down our rebellion and build up our faith and character. It is part of the way that he loves us.

I don’t think I was torturing my four boys when discipline sometimes included depriving them of comforts or causing them some physical pain or threatening them with either pain or deprivation. And don’t think my Army Ranger instructors were torturing me when they made me hungry and sleepy and uncomfortable in order to prepare me for surviving on the battlefield.

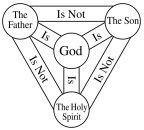

However, because many Americans have no category in their thinking for an eternal human spirit, they can’t differentiate the human will and the human spirit. As a result, the breaking of one appears no different than the destruction of the other. Ironically, this cultural blindness results in absolutist pronouncements, cookbook procedures, and rigid legalism masquerading as the “higher moral standard.” Situationally tailored enhanced interrogation that preserves human dignity requires differentiating the will and spirit.

This cultural blindness also results in the double standard that it’s moral to “drone” terrorists to death when they are in hiding, but it’s immoral to interrogate them in enhanced ways when they are in captivity. Principles of self-defense permit killing enemy combatants who are even in hiding, but killing enemies after they are captured is not self-defense and is not moral. Without the ability to differentiate will and spirit, destroying the will of captured enemies appears to be as immoral as killing them.

However, when the will and spirit can be differentiated, deprivation, humiliation, pain, discomfort, and threats of these conditions become neutral tools that can be used for either moral or immoral ends. What makes these tools for interrogation right or wrong isn’t what they intrinsically are, but how they are used. Are they used for a good purpose or for an evil one? Are they applied while preserving an attitude of love for the detainee or in an attitude of hate and vengeance?

The principles of just warfare, that are used to guide morality in war, can also guide morality for treating and interrogating detainees. Bombs and guns are not inherently evil. What makes them good or bad is how and with what motives they are used. Yes, sometimes the ends really do justify a means. Just as some things like faith and freedom are worth dying for, and other things like self-defense and restoring peace are worth fighting for, so these same things are worth interrogating for.

Just like spanking a child should not be done in anger, interrogations should be done in compassion and with self control. They should seek to break down the will without destroying the spirit. And they should situationally follow just war principles rather than rigid cookbook procedures and politically expedient formulas. As in just warfare, the degrees and means of confrontation must be tailored to morally fit each presenting situation.

An interrogation that avoids torture will, therefore, be just in its cause (jus ad bellum) and just in its means (jus in bello).

In just war tradition, being just in cause implies it will be the following:

- A response to imminent threat in order to either

- protect oneself (national self defense)

- protect innocent life (law enforcement)

- Chosen and executed by a competent authority (i.e. a legitimate government)

- Chosen formally with clear intentions that are

- to restore peace, not destroy the detainee

- not from vengeance, cruelty, hatred, jealousy, or power

- in accordance with national consensus

- Chosen as last resort after all other options ruled out (not necessarily all other options tried)

- Reasonably able to succeed

- Preventing more evil than it causes

And in just war tradition being just in means implies the following constraints:

- Proportionality – using the minimum force necessary to succeed

- Safeguards uninvolved personnel (i.e. not harming relatives of the detainee)

- Respects the sanctity of life

- recognizes interrogator and detainee as morally equal

- accepts similar treatment for oneself given reversed circumstances

These principles show how in some circumstances even light treatment can become torture, while in other situations very heavy treatment is morally proper.

Our western culture, which separates the relevance of spiritual and material realities as aggressively as it separates church and state, handicaps us in defining torture just as it handicaps us in spanking children. Because many Americans cannot differentiate will from spirit, the breaking of one appears no different than destroying the other. Ironically, this materialistic cultural blindness results in absolutist pronouncements, cookbook procedures, and moral ultimatums more typically attributed to legalistic religious fundamentalists than to supposedly sophisticated relativistic and tolerant post-modern progressives. Counter-intuitively, it is religion rather than materialism that undergirds sophistication, tolerance, and relativism when it comes to interrogating terrorists.

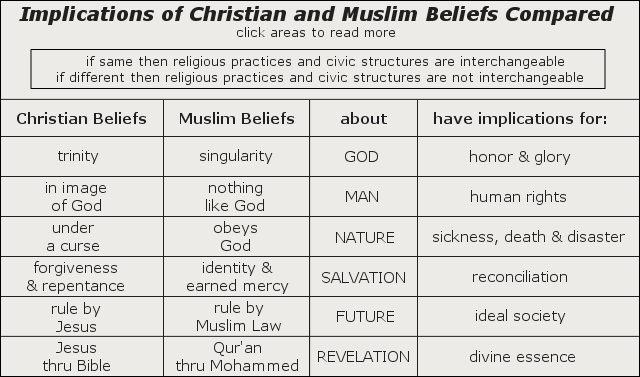

This is the first in a series comparing the social impact of theological differences between Christianity and Islam.

This is the first in a series comparing the social impact of theological differences between Christianity and Islam.

http://www.faithandwar.org

http://www.faithandwar.org Mark Durie's Blog

Mark Durie's Blog Military Missions Network

Military Missions Network The Christian Fighter Pilot

The Christian Fighter Pilot The Navy Christian

The Navy Christian