Printable pdf Version

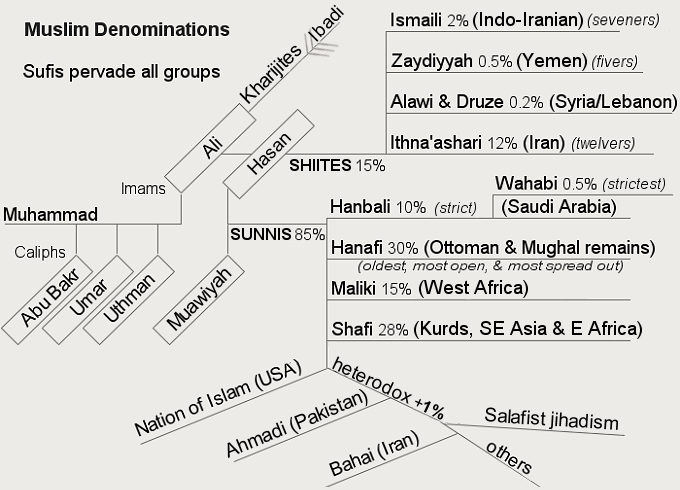

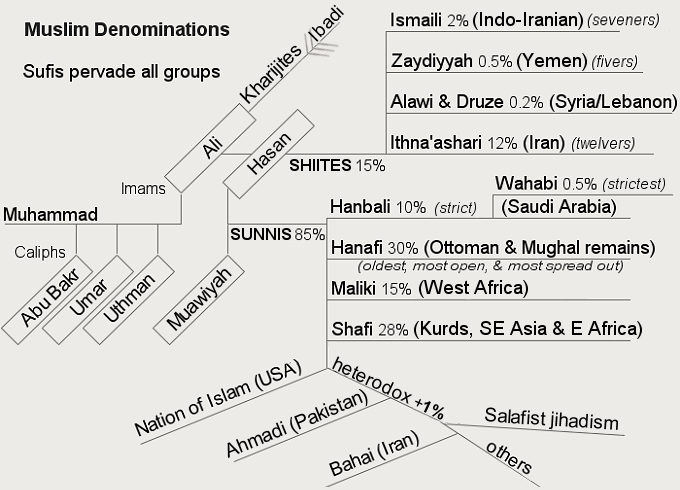

The clickable charts below overview a complex topography of competing Muslim institutions and complex trans-institutional Muslim movements.

Institutional Development of Islam

Click different regions to learn more about sects and movements in Islam.

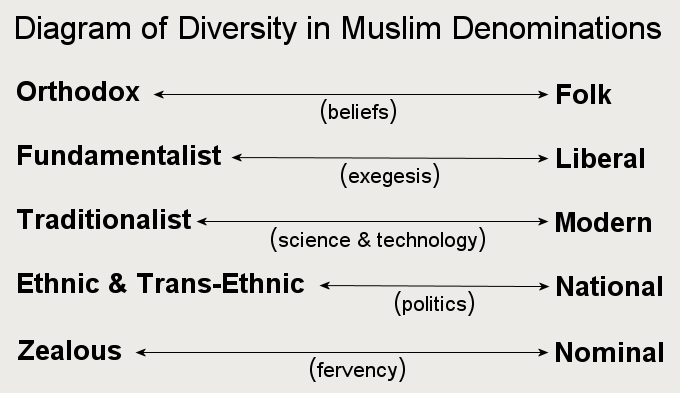

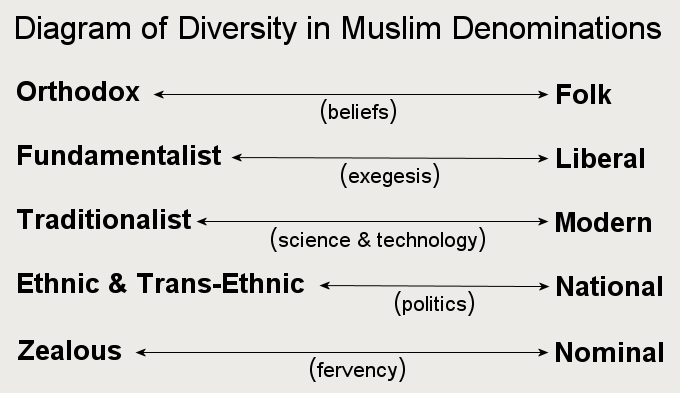

The diagram below illustrates

Diversity Within Muslim Institutions

Two individuals in different denominations may be more alike than two individuals in the same. Regrouping along these five different sliding scales produces the modern movements within Islam that are creating tension and new institutions.

Click different regions to learn more.

Belief Scale – Orthodox to Folk:

In Indonesia our house helper warned us to hang a clove of garlic around the neck of our 6-month old son whenever we might take him with us into the market. A few miles from our house, the tomb of the missionary who’d established Islam in that part of Indonesia attracted everyone from barren women praying for a child to students praying to pass exams. What most educated Americans consider superstition affects most Muslim lives more than the five ritual “pillars” of Islam. Charms of the evil eye and the hand of Fatima abound even in modern Turkey. Saddam Hussein had reportedly worked some magic that would protect him from bullets. Scholars call these expressions “Folk Islam.” Many clerics claim the Qur’an forbids Folk Islam and the beliefs attached to it. In the early 1800s, Wahabi-influenced pilgrims returning from Mecca started a war in Sumatra against the traditional aristocracy to purge heterodox folk practices. Similar sentiment impacts many today. On the belief scale, most Muslims lean folk. Most religious leaders lean orthodox. . (Back to Diagram)

Exegesis Scale – Fundamentalist to Liberal:

After 9-11 on September 16th, Al-Muhajiroun released a statement to the press praising the Taliban for their work towards establishing Shari’a. It called upon all Muslims to support them. Two days later, the flagship English language newspaper of Bangladesh ran an article saying that no true Muslims anywhere can support such terrorism because “Islam is a religion of peace.” The difference in these two statements flows from methods of interpreting scriptures. For exegetical fundamentalists, scripture is “the” authority to be taken at face value and interpreted independent of cultural context and history. For exegetical liberals, scripture is “an” authority to be balanced with knowledge from other sources. Strong liberals prefer allegorical and figurative interpretations. Strong fundamentalists prefer literal ones. In Surah 9 verse 5, the Qur’an says to slay, capture, besiege, and ambush non-Muslims unless they repent and submit. At the fundamentalist extreme, this verse calls for jihad against Americans and Jews. A more liberal approach studies the context and discerns that this verse should not be applied in that way. Irshad Manji sits at the liberal end of the exegesis scale. She is a Muslim, a Canadian, a speaker, and an author. She produced and hosted the Gemini award-winning show QueerTelevision, and she is lesbian. Osama bin-Laden sits at the other extreme. Most Muslims are in the middle. Most political leaders lean liberal. Most common people lean fundamentalist. Religious leaders span the whole spectrum. (Back to Diagram)

Science & Technology Scale – Traditionalist to Modern:

Extremes on this scale become most apparent in the fields of medicine and education. In Indonesia, when they got sick, some of our friends turned first to herbal cures and witch doctors. Others turned first to state-of-the art imported medical technology. Some sent their children to boarding schools with European style curriculum. Others boarded their children at schools committed to the conviction that everything anyone ever needed to know was in the Qur’an. Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) is the largest religious organization in Indonesia and one of the largest of its kind in the world. It leans traditionalist. Its schools follow the traditional pesantren Muslim boarding school model. They teach religion as traditionally taught and practiced in Indonesia. Many of its leaders practice a pre-Islamic Javanese mysticism called Kebatinan. Modernist leaning Muslims would consider it to be vain superstition. Before its national assembly meetings, NU has been known to sponsor an exorcism of the facilities. Muhammadiyah is Indonesia’s second largest religious organization. It leans more modern. Its schools are more European in style, curriculum, and methods. It opposes unorthodox syncretism to pre-Islamic beliefs and practices while embracing a more modern view on gender equality. It seeks to reform Islam, as it has been traditionally taught by the ulema, in order to to make it more relevant in the modern world. On the scales addressed so far, NU leans folk, liberal, and traditionalist. Muhamadiyah leans orthodox, liberal, and modern. On the remaining two scales, both emphasize nationalism and fervency. (Back to Diagram)

Political Scale – Ethnic/Trans-Ethnic to National:

Position on this scale depends on personal identity and group allegiance. Heads of state as well as nearly all politicians and government workers land solidly at the national end. Translators working with coalition forces to stabilize Afghanistan and Iraq land on the national end as well. At the opposite extreme would be someone like bin-Laden who cares nothing about either political borders or ethnicity. He envisions an imperial Islam, like in the days of old, transcending ethnic identities and nation-state boundaries. For many Muslims, like for most Kurds, ethnic and tribal identities transcend both national and religious ones. Among many Muslims, ethnicity and religion cannot be separated. The name Minangkabau for a tribe in Indonesia means “winning buffalo.” Minangkabau people say that if a Minangkabau person leaves Islam, all that remains is the buffalo. The saying means that when a Minangkabau person leaves Islam, that individual ceases to be a person in the ethnic group. (Back to Diagram)

Fervency Scale – Zealous to Nominal:

The vast majority of Muslims are peaceful, and, “co”-incidentally, the vast majority of Muslims are nominal. Of the two billion people who claim to be Christians only a very small percent attend church regularly or give sacrificially to religious causes. The same is true for one billion Muslims. The percent faithfully keeping the pillars and sacrificially donating to charities is small. Being zealous does not equal resorting to violence, but it heightens that risk. Fortunately, Jesus understood human nature enough to teach strongly against violence in his name, and he set a solid example of non-violence. Historically, many Christians still have not followed his example. I am not qualified to teach about Islam or the life of Muhammad, and I will not do that. I can, however, teach about Jesus, current events, and history. Around the world we see that when Muslims turn zealous because they have been offended over something like cartoons of Muhammad, they often resort in very large numbers to using violence in the name of Islam. Being zealous in a faith does not make one violent in that faith’s name, but the tendency to violence in the name of a religion will be higher among the zealous believers than among the nominal ones. (Back to Diagram)

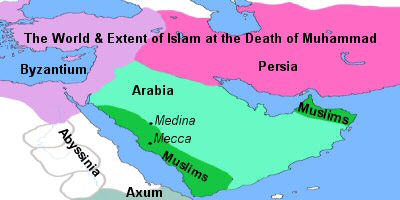

Muhammad (570-632):

He is the founder of Islam. Muslims regard him as the last and greatest of four prophets who dictated divine scriptures. The other three were Moses, David, and Jesus who delivered the Taurat, Zabur, and Injeel respectively. Mohammad revealed the Qur’an, the supposed last and only undistorted scriptures available today. He and his followers were persecuted in Mecca. In 622, he and his followers fled to Medina. This event marks the beginning of the shorter lunar Muslim calendar year. In Medina, Muhammad established his political as well as religious rule. In 630, he returned with a larger following to conquer Mecca and unite the Arab tribes under Islam as a religious and political system. He died from illness in 632. Muhammad’s closest followers (and followers of those followers) recorded his non-revelatory acts and sayings. These writings are called Hadiths. They establish precedents for interpreting the Qur’an into Shari’a law. (Back to Chart)

Abu Bakr (573-634):

He was the father of Muhammad’s third and favorite wife, Aisha. He was a close companion and advisor to Muhammad. He subdued rebelling tribes at Muhammad’s death in 632 and ruled as Islam’s first Caliph until his death from illness in 634. He compiled the Qur’an from various scraps of paper and other materials upon which Muhammad’s revelations had been written. He then forbid revising his “authorized” copy. He invaded Sassanid Persian and Byzantine empires. He expanded the emerging Caliphate into parts of modern Syria and Iraq. (Back to Chart)

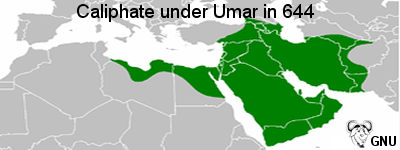

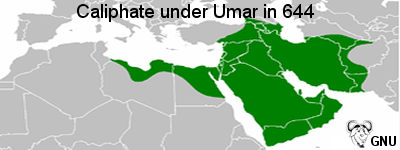

Umar a.k.a. Omar (c. 590-644):

He took over as the second Caliph the day that Abu Bakr died in 634. He had been a close companion of Muhammad. He was an expert jurist and military commander. He became one of history’s greatest political geniuses. He expanded the Caliphate taking over the whole of the Persian Empire and two-thirds of the Byzantine Empire. Many non-conforming Christian groups (i.e. Maronites, Jacobites, Copts, Nestorians) initially welcomed the Arab liberation from Byzantine intolerance. He laid the foundation for administrating non-Muslim majorities that preserved Muslim imperial expansion. He developed a reputation for ruling justly over Muslims and non-Muslims alike. For example, he allowed Jews to live and practice Judaism in Jerusalem where it had been forbidden for 500 years. At the peak of his power in 644, he was assassinated. (Back to Chart)

Uthman a.k.a. Usman (579-656):

He took over the growing Muslim empire as the third Caliph upon Umar’s assassination in 644. He had been a close companion of Muhammad. He expanded the Caliphate, instituted economic reforms, and expanded public works. He put down revolts in Persia, resisted attacks from Byzantium, prepared to invade Constantinople, and expanded into Crete, Sicily, Cyprus, Nubia, and the Iberian Peninsula. During his rule, differences in content of the Qur’an began to emerge in various parts of the empire. He obtained from Muhammad’s fourth wife, Hafsa, a copy of what Abu Bakr had assembled. Copies were sent to each province with orders to destroy all others. While featuring economic and military success, he faced intrigue and political unrest. In 656, rebels besieged him in his own home in Medina and assassinated him. (Back to Chart)

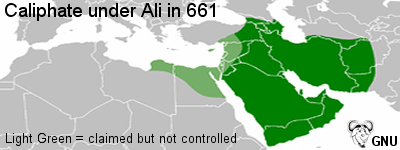

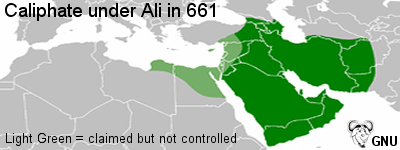

Ali (c. 600-661):

Ali is Sunni Islam’s fourth Caliph and Shia Islam’s first Imam. He succeeded Uthman to become fourth Caliph in 656. He was not universally accepted as caliph, resulting in the empire’s first civil war. In 661, he accepted truce with opponents by arbitration. A member of a faction that opposed the arbitration assassinated him. Ali was both Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law. Because of this blood relationship through which Muhammad has grandchildren, Shia Muslims accept Ali as Muhammad’s correct successor. They view Abu Bakr, Umar, and Uthman as usurpers. (Back to Chart)

Hasan (626-669):

He is Ali’s oldest son. Muhammad is his grandfather. He reigned for less than one year in 661 as fifth Caliph. For Shiites, he is the second Imam. After a few minor skirmishes between major opposing armies, he ceded the title of Caliph to Muawiyah in exchange for peace. Hasan was poisoned by one of his wives in 669. His younger brother, Hussein, followed him as Shia Islam’s third Imam. (Back to Chart)

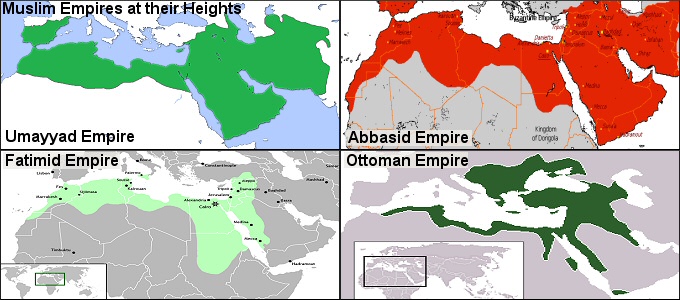

Muawiyah (602-680):

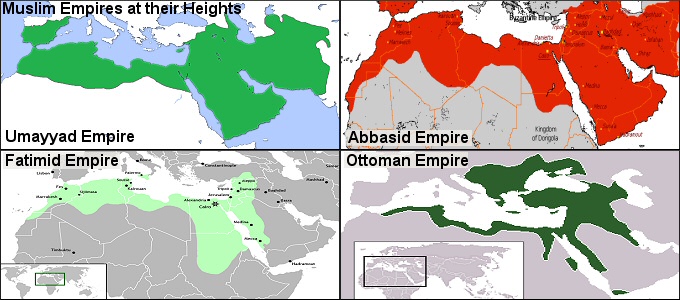

He was governor of Damascus and Uthman’s cousin. In 656 he contested Ali’s selection to be the fourth Caliph and instigated civil war. After Ali’s murder in 661, he took the caliphate from Ali’s oldest son, Hasan. This marked the division between Shia and Sunni Islam with Hasan heading the Shiites as their second Imam and with Muawiyah heading the Sunnis as their fifth or sixth Caliph depending upon whether or not Hasan is counted as the fifth Caliph. He founded the Umayyad caliphate, which ruled from Damascus until defeated by the Abbasids of Baghdad in 750. His dynasty governed the largest Arab-Muslim state in history and the world’s sixth largest contiguous empire ever. (Back to Chart)

Kharijites:

These are the first schismatic sect of Islam. They accepted the caliphates of Abu Bakr and Umar, but rejected and rebelled against Uthman. They initially accepted Ali, but then rejected him over his accepting the arbitration that ended the first civil war. They believe in obedience to the Caliph as long as he rules justly and piously. If not, they believe the Caliph must be confronted, deposed, or even murdered in order to be replaced. Ali’s assassin was a Kharijite. They eventually split into more than twenty sub-sects. Of these, only the Ibadi remain today. (Back to Chart)

Ibadi:

The last remaining Karijite sect. Mostly found in Oman. Smaller communities are also found in Algeria, Libya, and Zanzibar.(Back to Chart)

Caliphs:

These were heads of state and supreme religious leaders of the Muslim community ruled by the Shari’ah law. Shia Muslims reject all caliphs except Ali and Hasan. After the first four caliphs, who were personal friends of Muhammad, the title went to the members of the Umayyad (Damascus), Abbasid (Baghdad), Fatimid (Cairo), and Ottoman (Istanbul) dynasties with occasional competition from dynasties in Spain, North Africa, and Egypt. Regional governors were called sultans or emirs and ruled under the caliph. Muslims have not had a caliph since the end of the Ottoman Empire in 1924. (Back to Chart)

Imams:

These are the spiritual, political, and hereditary successors to Muhammad according to Shia Islam. Though human, they were infallible. They ruled with perfect justice and perfectly interpreted divine law. Their words and actions have become the model for everyone to follow. (Back to Chart)

Shiites:

The Shia faith is vast with various theological beliefs, schools of jurisprudence, philosophical beliefs, and spiritual movements. Shia Islam breaks with Sunni Islam primarily over its system for interpreting divine revelation and implementing political authority. In Shia Islam, the religious/political leaders are divinely selected and divinely inspired to infallibly interpret revelation and govern accordingly. (Back to Chart)

Ismaili:

They are called “seveners” by their detractors because they believe the Imamate ended with the seventh Imam Ismail ibn Jafar whose son disappeared to one-day apocalyptically return as the Mahdi. They also have seven rather than the five pillars of practice that are present in most other forms of Islam. They were once the largest Shiite branch. The Cairo-based Fatimid dynasty of the tenth century was Ismali. Today’s Ismalis fall into several different traditions or paths called tariqah. The largest is the Nizari path. It recognizes a living “Imam” as the 49th hereditary Imam. Though mostly Indo-Iranian in modern times, they also live in India, Pakistan, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, China, Jordan, Usbekistan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, East Africa, and South Africa. Many have emigrated to Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and North America. (Back to Chart)

Zaidiyyah:

They are called “fivers” because they follow the teachings of a different fifth Imam named Zayd ibn Ali. They embrace all the other eleven of the Shia imams. Unlike other Shia Muslims, they don’t believe the Imams were infallible or that they received special divine guidance. The Zaidi divide into three main groups. The largest group makes up over forty percent of Yemen. One Zaidi group in northern Yemen is revolting against the central government creating a humanitarian crisis there. (Back to Chart)

Alawi:

They call themselves Shia and take their name from Ali. Orthodox Sunni Muslims consider them to be completely heretical. They keep many of their distinctive beliefs secret. They are a powerful religious minority in Syria where they control many key positions in the military and government, like the presidency. Over one million live in cities throughout Syria and another million live in neighboring regions of Turky. They are one of the eighteen recognized minorities in Lebanon where they mingle with the Druze. (Back to Chart)

Druze:

They started as an Ismaili movement during the Ismaili Fatimid dynasty early in the eleventh century. They drew heavily from Greek philosophy and Gnosticism. They opposed some major trends in the religious landscape of their day. They have always been a minority. They have been alternately used and abused by the prevailing powers, sometimes rising to prominence and sometimes suffering vicious persecution. Today they remain socially and religiously distinct. They often conceal their beliefs and identity. They forbid intermarrying. Since 1043, they have forbidden proselytizing. Worldwide their population probably reaches one million. Lebanon, Israel, and Syria treat them as a separate community with their own religious court system. They have an important role in the politics of Lebanon. In Israel, some live in separate communities while others have citizenship and have served in the armed forces. Five Druze lawmakers are serving in the 18th Knesset. Unlike most other Muslims, they reject tobacco and polygamy as well as alcohol and pork, and they believe in reincarnation. They believe rituals are purely symbolic for an individualistic effect, so the pillars of Islam are not obligatory for them. (Back to Chart)

Ithna’ashari:

They represent 85% of Shia Islam. They are called “twelvers” for adhering to a progression of twelve imams in the lineage of Muhammad through his daughter Fatimah and son-in-law Ali. The imams were chosen by God and not by human consensus. They infallibly interpreted and applied Muslim law. They reject legal precedents set by Sunni caliphs. They believe every age has a divinely selected Imam. The imam for this age is the twelfth who was born in the ninth century. He has been supernaturally preserved and hidden. He will reappear someday to establish a correct and global Islam just before the final day of judgement. This is Iran’s national ideology. Most twelvers live in Iran and spill into neighboring Iraq, Azerbaijan, and Afghanistan. Significant twelver minorities live in Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Bahrain, Kuwait, and Lebanon. (Back to Chart)

Sunnis:

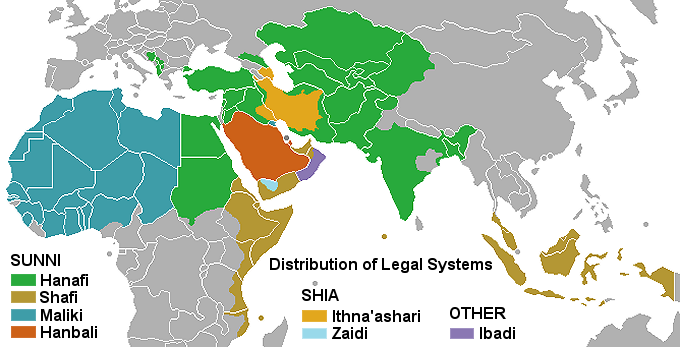

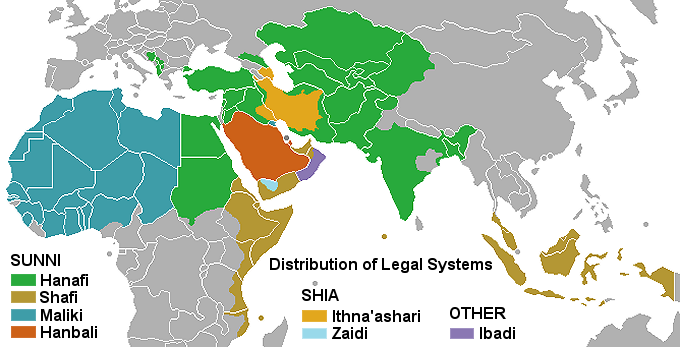

Both Shia and Sunni Muslims hold the Qur’an to be the ultimate authority for faith and practice. Both revere the acts and sayings of Muhammad (Hadith) as the key to interpreting and applying the Qur’an. Sunni and Shia Muslims differ over who gets to do the interpreting and applying. Shia Muslims conform around the identity and teachings of their imams. Sunni Muslims conform around the consensus of scholars who interpret and apply the Qur’an in accordance with what they identify as the Sunnah – the tradition of Muhammad and of the emerging Muslim community. As Shia Muslims ascribe infallibility to their imams, so Sunni Muslims ascribe infallibility to scholarly consensus, resulting in interpretations and applications that cannot be changed. Four legal traditions and three theological traditions have evolved from Sunni scholarly consensus. The legal traditions concern applying th Qur’an to everyday life. They are Hanbali, Hanafi, Maliki, and Shafi. The theological traditions concern the nature of God, revelation, man, and fate. These are Ash’ari, Maturidiyyah, and Athari. Ash’ari tradition emphasizes divine revelation over human reason for determining ethics, and it emphasizes divine sovereignty over free will for determining fate. Maturidiyyah tradition reverses Ash’ari emphasis by more highly esteeming human reason and free will. Athari tradition is more intuitive, anti-intellectual, and tolerant of ambiguity than the other two. (Back to Chart)

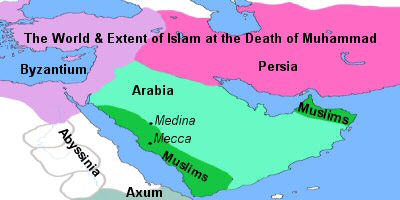

See more detailed source map here.

Hanbali:

Students of Imam Ahmad bin Hanbal started this tradition around 855. It is the strictest and most literal in its approach to the Qur’an. It has the smallest number of followers. It predominates in the Arabian Peninsula. It prefers the Ash’ari theological tradition that elevates divine revelation above human reason for formulating ethics and divine sovereignty above free will for determining fate. (Back to Chart)

Wahabi:

Wahabism is the strictest sect of Hanbali Islam. It is primarily practiced in Saudi Arabia, and it is exported from there with oil profits. Abd al-Wahab started it in the 18th century. He advocated restoring Muslim practices to the days of the prophet and his imperial successors. He sought to purify Islam of syncretism and of what he considered to be later innovations. When pilgrims influenced by Wahabism returned to Indonesia in the early 1800s, they instigated revolution not only against the Dutch but also against traditional aristocracies. (Back to Chart)

Salafi jihadists:

Salafi Muslims want just like Wahabi Muslims to return to the “perfect” Islam that was practiced in the days of Muhammad and his companions. The terms Salafi and Wahbi are often used interchangeably. Salafism differs from Wahabism (and is more dangerous) by drawing from all four of the legal systems in Sunni Islam. Salafists describe themselves as “Muwahidoon”, “Ahl al-Hadith”, or “Ahl at-Tawheed” (listen for these terms). Salafists reject calling themselves Wahabists. They contend Abd al-Wahab did not go far enough because he did not restore the pure Islam. Salafis usually reject Western ideologies such as Socialism and Capitalism as well as concepts like economics, constitutions, and political parties. They seek to advance Shari’a (Muslim law) rather than a Muslim political program or state. Salafi ideology represented in Sayyid Qutb is producing schismatic jihadists like Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri. (Back to Chart)

Hanafi:

Followers of Abu Hanifa an-Nu’man ibn Thabit established this jurisprudence tradition around 780. It is the oldest of the four systems. It emphasizes human reason. It is the most liberal of the four schools, and it has the largest following. The Ottoman Empire ruling from Istanbul and the Mughal Empire ruling the Indian subcontinent used and spread this system. It is the most popular system nearly everywhere they ruled. (Back to Chart)

Maliki:

Two literary works by Imam Malik (711-795) inspire this jurisprudence system. It predominates in West Africa, North Africa, the United Arab Emirates, and parts of Saudi Arabia. Around fifteen percent of Muslims follow this system. It’s main distinctive comes from ascribing more weight to sources originating in Medina and precedents established there than sources and precedents derived from other early Muslim communities. (Back to Chart)

Shafi:

This is the second most widespread Muslim legal system. It’s name comes grom Imam ash-Shafi’i. His categories for legal reasoning included a secondary place for community consensus and analogy in addition to the Qur’an and Sunnah. Shafi jurisprudence is the official system for the governments of Brunei, Malaysia, and Indonesia. It is also predominates in Syria, Palestine, Lebanon, the U.A.E. Chechnya, Kurdistan, Egypt, Djibouti, Eritrea, Somalia, Yemen, Sudan, the Maldives, and Singapore. (Back to Chart)

Bahai:

This is a monotheistic faith founded in nineteenth-century Persia by a man claiming divine inspiration and the title Baha’ullah. Followers assert they follow a distinct and new religion. Most Muslim political and religious leaders do not concur. They say it is an apostate form of Islam. Followers have been severely persecuted in Iran and Egypt where their religious activities are illegal. Since Islam claims to be the last and final divine revelation, new religions are often less tolerated than old ones. Bahai followers view their heritage in Shia Islam to be similar to the heritage of Christians in Judaism. Worldwide followers number above seven million. Over two million live in India. The rest are widely distributed among all the world’s nations. Over 300,000 of them form the largest religious minority in Iran. (Back to Chart)

Ahmadi:

In the late 1800s, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad claimed to be the promised Jewish Messiah, second coming of Christ, and the Muslim Mahdi. He started the Ahmadiyya movement in British occupied India/Pakistan as a branch of Islam. His followers today claim to be Muslims leading the revival and peaceful propagation of true Islam. They predominantly live in Pakistan, Indonesia, and India. They have freedom in India, but are persecuted in Pakistan and Indonesia. Orthodox Muslims consider them heretics for embracing a prophet that followed Muhammad. (Back to Chart)

Nation of Islam:

Wallace D. Fard, a.k.a Elijah Muhammad, founded the Nation of Islam (NOI) in Detroit in 1930. He aspired to restructure the conditions of black men and women in America. He claimed to be the Mahdi of Islam and second coming of Christ. Louis Farrakhan heads the religious organization today. The NOI preaches adherence to the pillars of Islam, but its followers do not practice them in accordance with traditions in Islam. Many NOI teachings about God and mankind are not in accordance with mainstream Islam. (Back to Chart)

Sufis:

Sufism pervades every denomination of Islam at varying percent levels. It results in an inner mystical and experiential manifestation of personal spirituality that is outside of orthodox Muslim law and theology. Sufi movements span languages, cultures, continents, and a thousand years. Participants usually seek divine love and knowledge. They typically exhibit discipline and piety. They commonly use dancing, trances, chanting, and singing. They frequently venerate local saints at their tombs. Sufis are organized into brotherhoods around spiritual leaders and grouped into orders called tariqas. (Back to Chart)

Militaries of the world have always been at the leading edge of intercultural relations and security remains one of America’s most significant exports. If professional exposure to some of the neediest parts of the world creates ministry opportunities, then no segment of the Church in America is more strategically positioned for advancing the Great Commission than Christians who are in the U.S. military.

Militaries of the world have always been at the leading edge of intercultural relations and security remains one of America’s most significant exports. If professional exposure to some of the neediest parts of the world creates ministry opportunities, then no segment of the Church in America is more strategically positioned for advancing the Great Commission than Christians who are in the U.S. military. Tom and I served as Army Combat Engineer Lieutenants together in Panama in the early 1980s. Our wives became fast friends, and we shared lots of memorable experiences, both on and off duty. Tom and Robyn helped Lynn and me when we went to Indonesia for seven years. Today, we get to help Tom and Robyn as they head to Africa.

Tom and I served as Army Combat Engineer Lieutenants together in Panama in the early 1980s. Our wives became fast friends, and we shared lots of memorable experiences, both on and off duty. Tom and Robyn helped Lynn and me when we went to Indonesia for seven years. Today, we get to help Tom and Robyn as they head to Africa. Robyn and I are heading to West Africa with

Robyn and I are heading to West Africa with  I feel our life is like this puzzle to which God has given us one piece at a time. It’s for His purpose that we pull on these different puzzle-piece experiences as he leads us into the future. I have always felt the Lord preparing me for something beyond the Army. One of the greatest things that interested Wycliffe is what the military calls “leadership,” but missions agencies call “administration” or “management”. Wycliffe is a fairly large mission organization with many different entities around the world. They need folks with leadership experience and administrative skills to help run things at every level. That’s what got them interested in Robyn and me.

I feel our life is like this puzzle to which God has given us one piece at a time. It’s for His purpose that we pull on these different puzzle-piece experiences as he leads us into the future. I have always felt the Lord preparing me for something beyond the Army. One of the greatest things that interested Wycliffe is what the military calls “leadership,” but missions agencies call “administration” or “management”. Wycliffe is a fairly large mission organization with many different entities around the world. They need folks with leadership experience and administrative skills to help run things at every level. That’s what got them interested in Robyn and me.

http://www.faithandwar.org

http://www.faithandwar.org Mark Durie's Blog

Mark Durie's Blog Military Missions Network

Military Missions Network The Christian Fighter Pilot

The Christian Fighter Pilot The Navy Christian

The Navy Christian